As the national dialogue about race and social justice has grown louder in recent months, discussions and initiatives related to diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging are becoming increasingly prominent within the medical profession, according to Andrea E. Reid, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School.

“This is not a new conversation; these are old issues,” said Dr. Reid. “But some people want to have a deeper conversation now. The times are pressing individuals and institutions to have more substantive discussions and make lasting changes as it relates to diversity and belonging.”

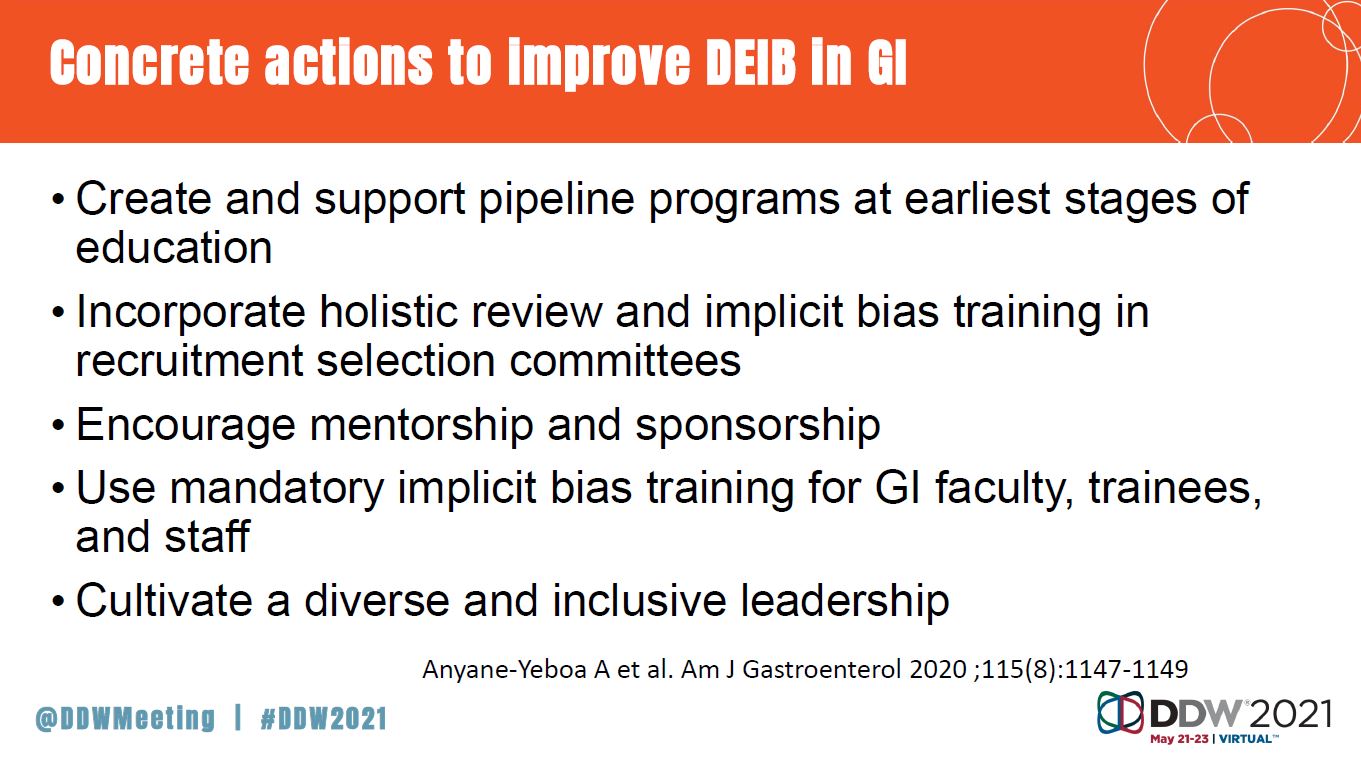

Dr. Reid noted several key points about how medical training and education programs can start moving in the right direction:

- Learning the lexicon. Reid emphasized the importance of understanding current terminology (e.g., structural racism, microaggressions, implicit bias, privilege, diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging) as a necessary first step to making progress.

“Diversity and inclusion are not the same but have been used interchangeably,” Dr. Reid said. “Diversity is about numbers and percentages. It is a fact. Inclusion is about making sure the culture embraces all people so that they can achieve their best outcomes. To use a well-worn analogy, diversity is like inviting various people to the dance; their experience is not the focus. Inclusion is inviting them onto the dance floor, to be engaged in the dance. And belonging — which should be the ultimate goal for all medical educational programs — is where people are not only embraced in the culture, but have the power to influence it. They’re in the room, on the dance floor, and they can actually contribute to the playlist.”

- Making a paradigm shift. To achieve diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging, medical institutions have to be willing to take an honest look at the extent to which these factors are missing in their programs. For example, the Harvard Medical School’s Program in Medical Education Task Force Against Racism — made up of both faculty and students — recently performed an in-depth scan of their activities to identify places where racism and bias is embedded into the program, and identified methods to make the program in medical education antiracist and to monitor progress.

“Every aspect of the program should be on the table: Who we admit, how we teach about race and racism within medicine, where we put our money, what research we fund and how we consider people for promotion,” Dr. Reid said.

- Taking individual action. Although these are longstanding inequities that require major systemic and institutional change, Dr. Reid offered individual strategies to help people become antiracist, such as educating oneself about race and structural racism, as well as learning and sharing how racism harms the medical profession.

AGA applauds all institutions and individuals who are taking steps to help make GI a more diverse and inclusive field. Learn about the AGA Equity Project, a multi-year effort spanning all aspects of AGA to achieve equity and eradicate disparities in digestive diseases.

Dr. Reid’s oral presentation of “Supporting inclusion and diversity in medical education” took place on Friday, May 21, at 3:30 p.m. EDT, as part of the AGA session “Race in Medicine and Science.”

One Response

I’ve seen that Asian students, extremely well qualified, are not

admitted to Harvard if the “quota” of Asians has been met !

This is as racist as it gets ! Tsk Tsk